When we travel, what do we take away from the places we see? Souvenirs? Memories? Do those places take something from us in exchange? Do they change us? Places and people are two ever-changing entities that interact constantly with each other, shaping each to the other’s whim. Of course it is obvious how mankind has shaped the earth, mapped it out, built cities and set aside places to preserve the nature that was there first. But I seek to explore how the earth shapes us, how each landscape we visit becomes a part of us in some way, and how we connect places with certain feelings and emotions. Why does the environment leave such an impression? And this divide established between humans and nature? Why is that so ingrained? Are we not natural creatures ourselves? Perhaps that is why we are so drawn to nature.

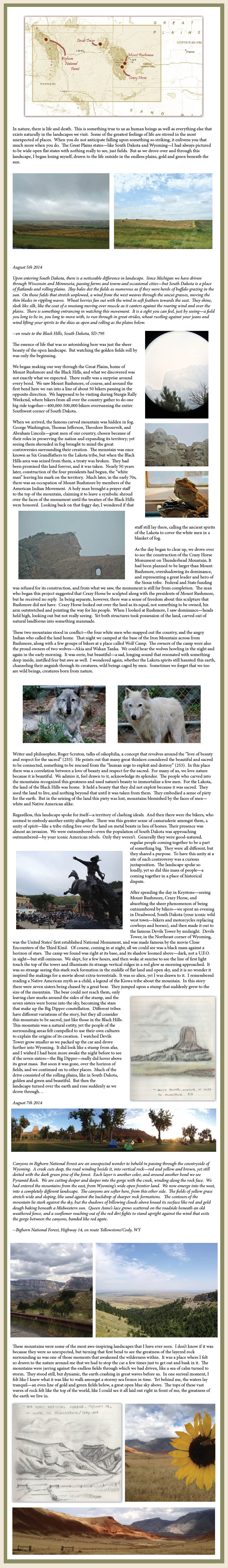

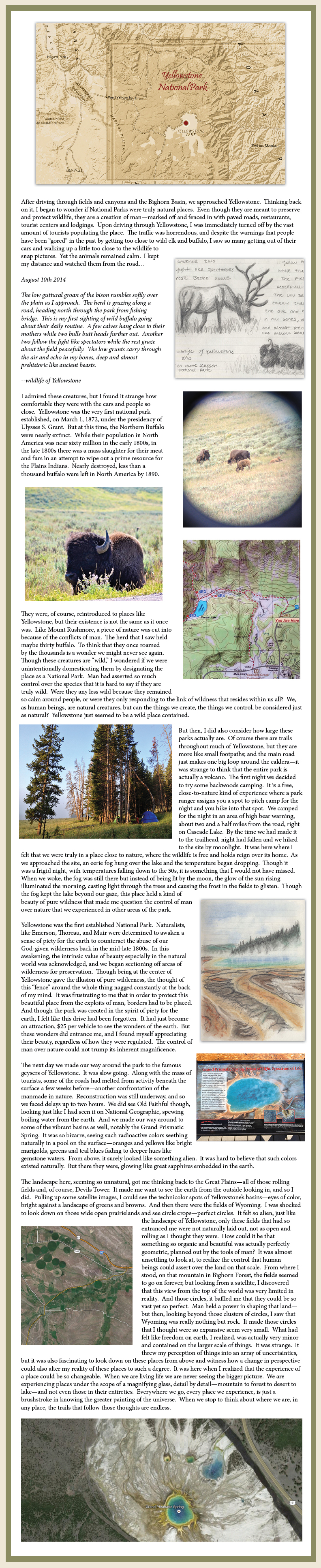

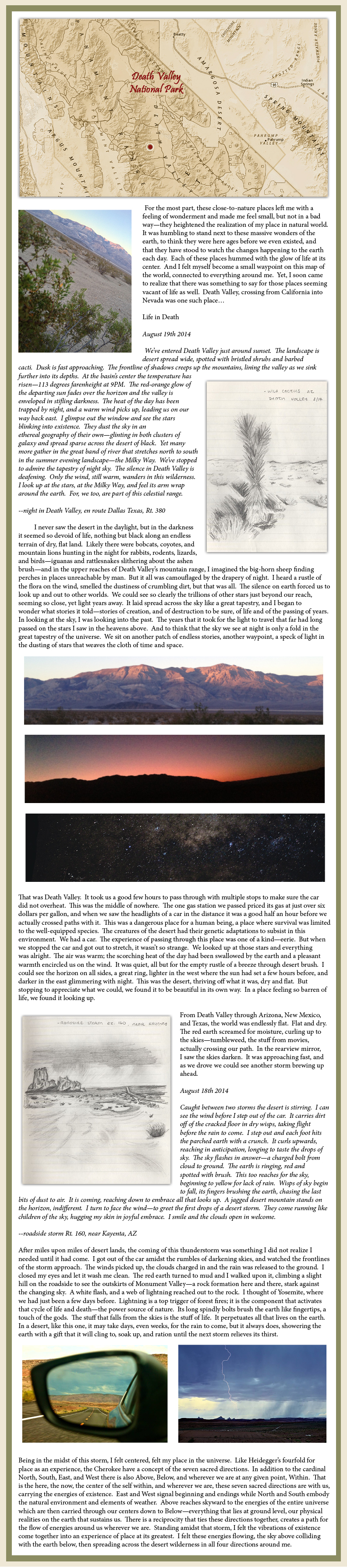

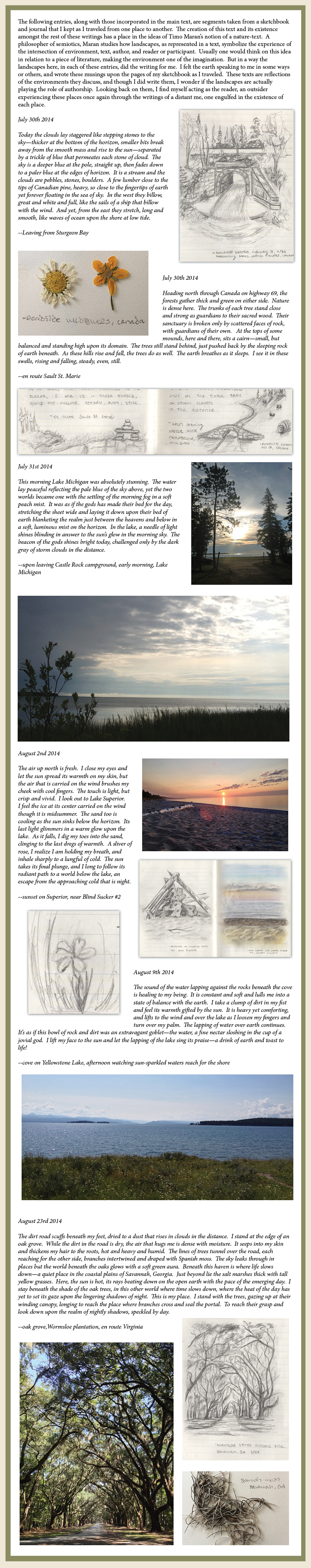

I spent a summer traveling around the United States—camping my way through, stopping at some of the most moving natural environments in the country. The northern lands of Canada and the Great Lakes region, Yellowstone National Park, the cool refuge of the Redwood Forests, The Grand Canyon, and the dry abyss that is Death Valley were just a few of the many places I experienced. I began to think about how each of the places I found myself in affected me personally, and how nature has a strong pull on the individual in general. There is something in nature that inherently is already a part of us as human beings. We are automatically drawn to the beauty of a sunset or a forest or ocean, and repelled by the destruction of a forest fire or drought. There is a stark connection here between humans and nature, and these instilled reactions make me wonder how strong that influence of place is on the self.

Yellowstone

The Redwoods

Yosemite

Death Valley

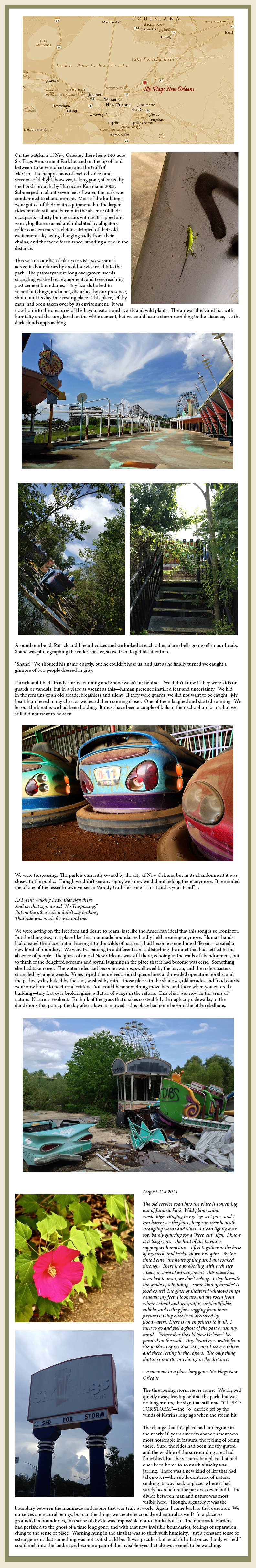

New Orleans

Conclusions

The Great Plains, Yellowstone, Redwoods, Yosemite, Death Valley, New Orleans

In the Great Plains I came to appreciate the beauty of a dynamic landscape rolling open and wide and rising to unexpected canyons—but also came to realize the power in symbolism that we attach to places—carving faces in mountains to immortalize man, using a natural monument to assert control over the land and each other. It was a place emanating with desire—desire to own the land, and desire to take it back—etched in the faces of four great Presidents and a determined Sioux leader upon mountains. In Yellowstone, I began to question our relationship with nature. Are we natural beings? Can the things we create be considered natural? What about National Parks? Can the wilderness that we fence off really be thought of as natural? Why is there this divide? Are we not natural beings ourselves? It was only in those deepest parts of Yellowstone, the backwoods, where I felt the wildness truly thrive, yet I did feel at peace with my surroundings, which made me question that divide even more. And then there was alienness of it all—the circle fields of the Plains, and the technicolor basins of Yellowstone. It made me realize how changeable our experiences of place could be.

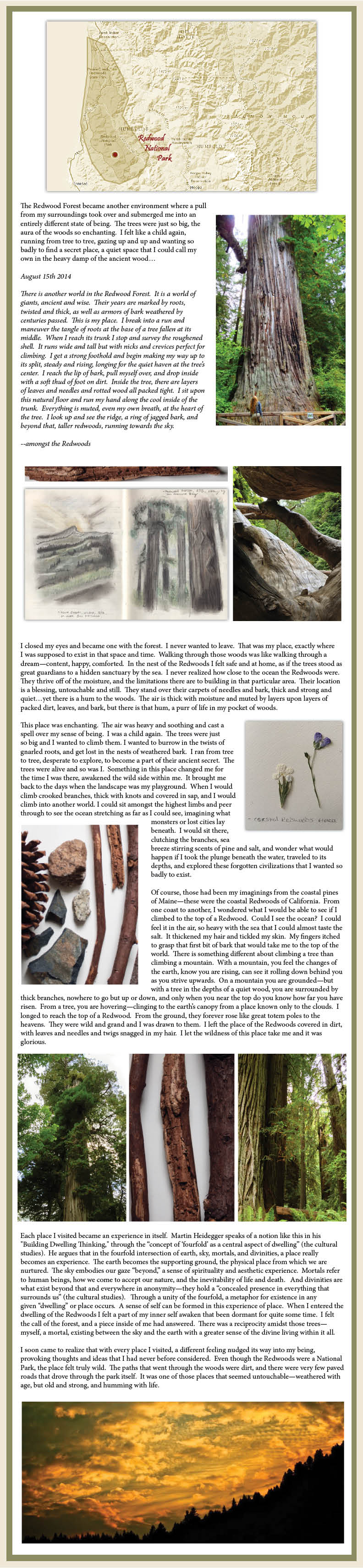

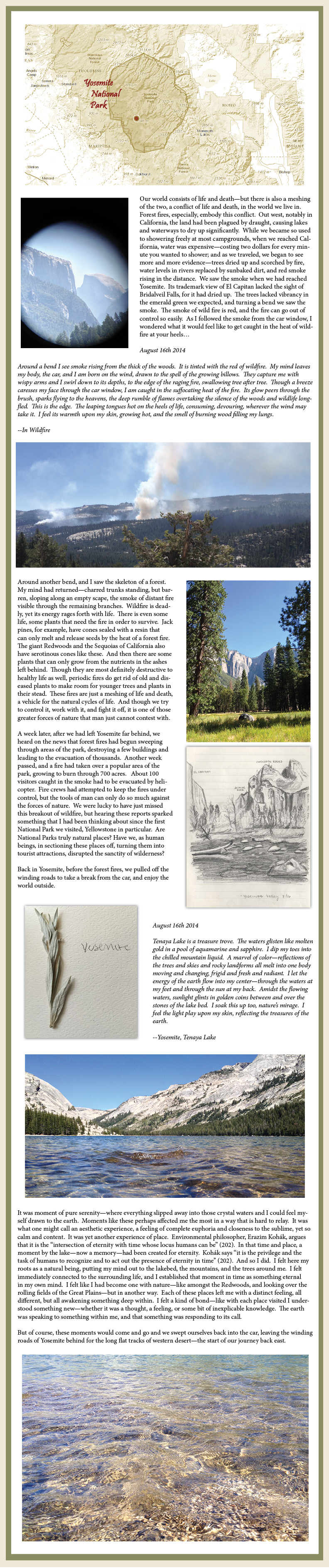

The Redwoods then altered my state of mind completely, took me back to when I was just a child, longing to explore and be lost to the enchanting trees. Climbing and feeling the earth packed beneath me, the air heavy with seaside moisture, and my spirit longing to be wild and free. And then there was Yosemite, whose forest fires provoked thought on the destruction and creation of life—how we try to fight it, control it, and work with it—while it is really a process meant to be left to its own, perpetuating the natural cycles of life. It brought back those same thoughts on Yellowstone—in sectioning off a National Park and controlling these natural fires are we disrupting the sanctity of nature?

And when the earth seemed devoid of life in desert lands like Death Valley, I recognized a calm quiet in the glimmering night, looking up and out to other worlds and feeling the greater pull of the universe in the life of distant stars. It was then that I realized nature extended even beyond the world we know on earth. Then finally, in the Deep South of New Orleans, there was the abandoned amusement park, a manmade attraction lost to the forces of nature nearly ten years ago with the coming of Katrina. Something created by the hands of men, destroyed by a hurricane and taken back into the arms of nature—a jungle of overgrown foliage and a home to the gators, lizards, and bats of the bayou. In its abandonment, this place became a refuge for those lesser beings of nature looking for a home.

But strangely, this last place tied everything together. It was vacant, but it was a different kind of emptiness than I had experienced in the desert night of Death Valley. It was the vacancy of something lost, perhaps the ghost of the childhood that was so awakened in the Redwood Forest. There was a sense of nostalgia in the park so tied to childhood, to the old thrills of youth, like the desire to climb those great trees—yet it was alien, strange to encounter in a place so changed, so ravaged by the forces of nature. It was another kind of estrangement, like what I felt from the satellite images of Wyoming. That was a rift from a god’s point of view, a change in perspective. Here in this park, I was seeing things, feeling them, up close. The wilderness that had flourished from an event of such destruction, flooding the city and this park along with it—this tied right back with Yosemite’s forest fires, nature destroying old life to make room for the new. I stood at the center of this jungle, rollercoasters, sky swings, and ferris wheel all drained of the life they once held, and replaced with something new, an overgrown habitat with a life of its own. And then there were the boundaries of this place to be considered, manmade and natural, reawakening all those questions that had arisen in Yellowstone.

With each of these places new thoughts and ideas, powerful feelings, seeped into my mind and being, and I realized that each of these places were connected with what we deem the natural world in one way or another. There is an undiscovered wilderness within ourselves that awakens when we are close to nature. It is a part of us—a calling that we cannot ignore. We are drawn to the life from which we are created and it exists everywhere we go. From the ever-changing landscape of the Great Plains to the subterranean volcano that is Yellowstone, from the thick enchantment of the Redwood Forest to the spreading wildfires of Yosemite National Park, from the driest of deserts in Death Valley to places like New Orleans ravaged by the floods of a greater force of nature. They are all so different, yet each one speaks to the soul—moving landscapes in a natural world that resonates with a wilderness within.

Other Journals

Leave a Reply