Illuminating Nature: A Manuscript Study

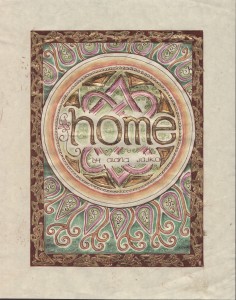

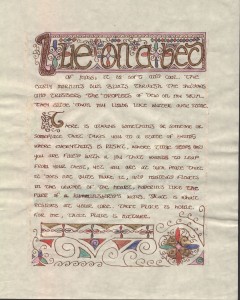

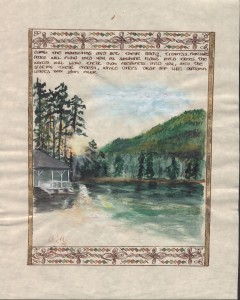

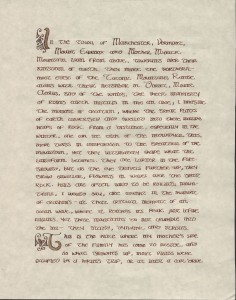

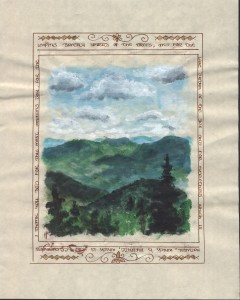

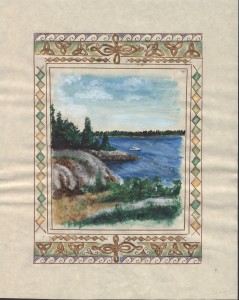

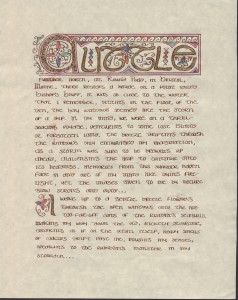

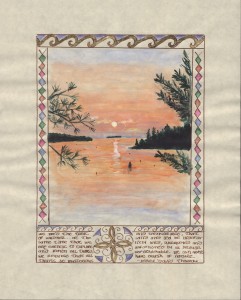

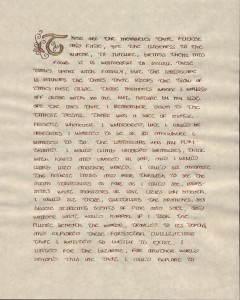

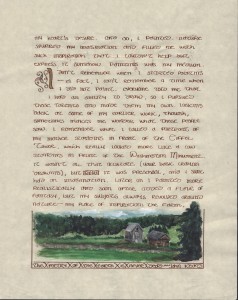

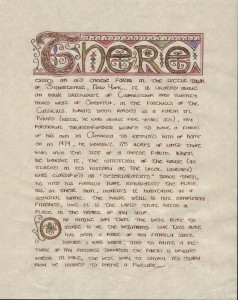

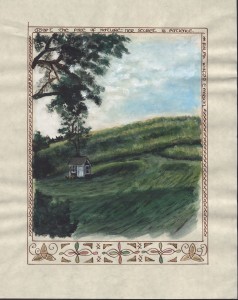

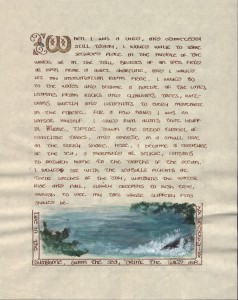

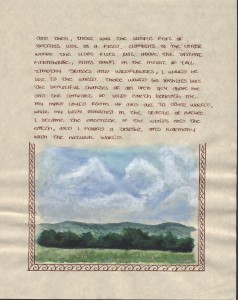

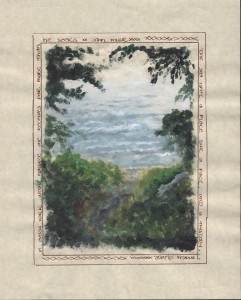

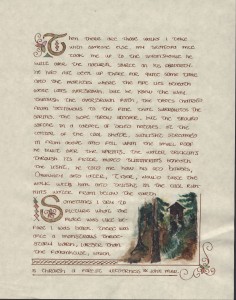

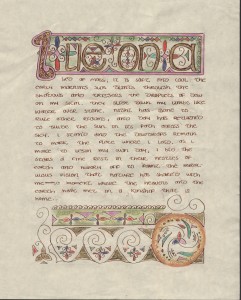

Medieval manuscripts are beautiful compilations of text and image. My work explores this media as a way to celebrate the beauty of the natural world, combining nature writing with marginalia and illustrations that reflect the content of the text. The calligraphy style is modeled after the font used in the Book of Kells, as it too portrays natural imagery throughout its pages. Manuscripts were meant to glorify the text within, and it is my hope to glorify and preserve an appreciation of nature in a world where it is sometimes overlooked.

Further Reflections

Illuminated manuscripts are classified as an art of antiquity. With their creation, the literature of the manuscript would be transformed into a work of art. In addition, illumination of the texts aided their preservation and informative value in an era when new ruling classes were not always literate. It made education more attractive and ensured the survival of important information throughout many ages.

The earliest surviving illuminated manuscripts are from the period AD 400 to 600, initially produced in Italy and the Eastern Roman Empire. Without documents such as these, most literature of Greece and Rome would have been lost in Europe; however, by aggrandizing these ancient documents, monastic scribes (whose task it was to create these manuscripts) succeeded in preserving text with beauty.

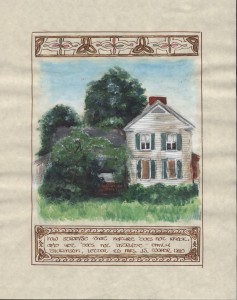

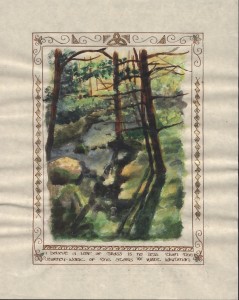

For my research I have conducted the construction of an illuminated manuscript, adapting ancient forms to my own contemporary interpretation. Since the process was first developed, illumination has grown and evolved differently from many eras to several cultures. The particular style that I have concentrated on is that of the Celtic culture in Ireland and Western Britain (classified as Insular art). Celtic illumination was highly influenced by the natural world. As a double major with English: Creative Writing and Studio Art, I find nature writing to be a genre of my calling, and this project seemed a great opportunity to combine my two areas of study with my interest in nature. By taking on this project it was my goal to recapture the beauty of a lost art and succeed in preserving an appreciation of nature in a world where it is sometimes overlooked.

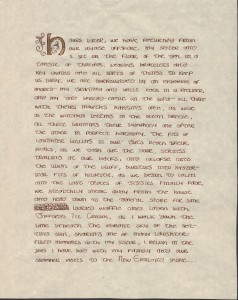

As the project came to a close, I could not believe how fast the weeks had flown by and how much I had accomplished over this time. When the research began, I was a novice in the art of calligraphy and the design that encompasses it. I remember being anxious to begin the manuscript, but I knew that the hours of practicing with different pens and methods were essential to creating the object I envisioned. Gold leaf was a new tool to me as well, and it is the very thing that makes a manuscript illuminated, so that required practice too. To dive into a completely foreign art form was strange, but exciting, and as the days moved forward, my hand moved more fluidly and the pages of the manuscript began to take shape.

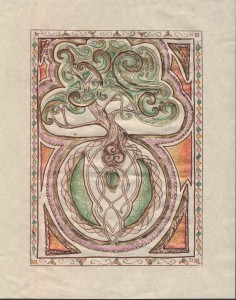

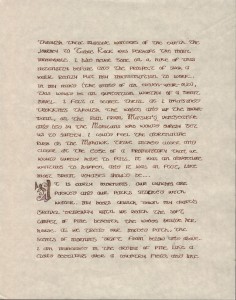

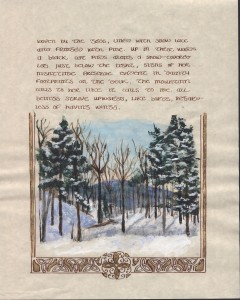

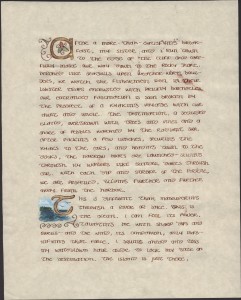

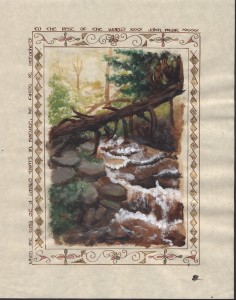

At first, I set aside whole pages for illustrations and left the text fairly plain with small designs here and there with the start of each paragraph; but as I grew more confident, I began integrating small scenes within the lines of text, and the letters at the start of each paragraph grew in size. I felt a kind of freedom with the pens and paints, eager to put images to the words I had written, eager to put to paper what my mind had envisioned. Then (as the subject of my text revolves around nature) I began to think about other writers and philosophers and naturalists and how they represented nature. It occurred to me to seek out these thoughts and include them as small quotes around illustrations or in the margins or borders of each page.

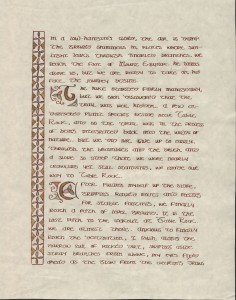

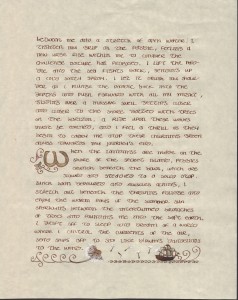

When I had gotten though all of the text, I felt like I had reached a milestone. The bulk of the work had been completed and it was time to return to each page and work on detail, erase the penciled guidelines, and work in more gold leaf wherever I thought a little more illumination could bring a page to life. I remember reading somewhere that these manuscripts were the equivalent to what we consider animations; the way the gold leaf shone beneath candlelight and the movement just from the designs alone really made them stand off the page and look alive.

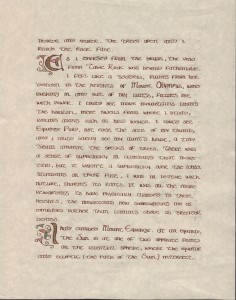

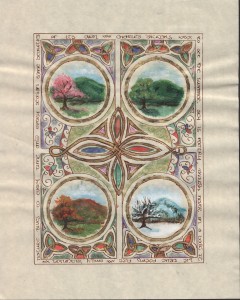

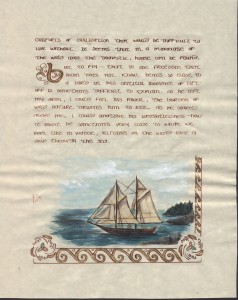

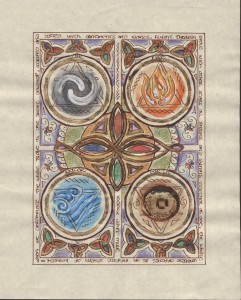

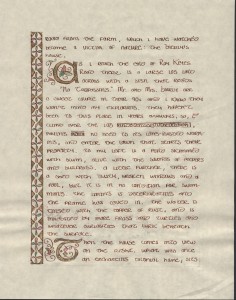

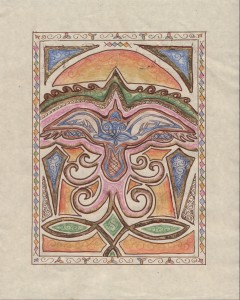

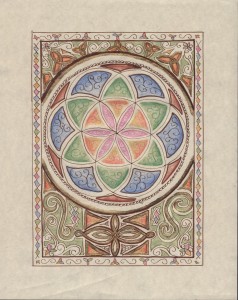

In the last week, I had been working on the “carpet” pages, which are abstract or meditative and involve more of the knot work and other geometric designs. In two of the pages I have represented the four seasons and the four elements. These are less of the abstract sort and are more of my own take on the carpet page. In the last few days, I had created three more pages. The first two center a tree in one and a bird in the other, depicted in more of the fashion you would see in the Book of Kells, which involves Celtic knots and curves and swirls. The final page is purely abstract and reminiscent of a stained glass window.

When it had come to the final week, I felt liberated to hold the manuscript in my hands and feel the weight of hours upon hours of penwork and painting. The concentration needed for such work has been a new experience for me, and I feel that I have now established a solid grounding in an art form that was so foreign to me at the start of my research. Overall the process has been rewarding, and I have a new appreciation for the amount of work required to create a manuscript as decorative as the Book of Kells. Even with the conveniences of cartridge pens and premade ink the project was an endeavor, and I can imagine the years it would have taken ages ago, when inks had to be mixed from berries and herbs and pens had to be fashioned from quills, all done by light of day or by flickering candlelight.

Leave a Reply